SOIL PREPARATION is the foundation of any successful garden. Too often, the eagerness to get our seeds in the ground, to watch those first sprouts reach up towards the sky – soaking in the sun’s rays – exclaiming victory to the gardener in our quest to create new life, sustenance and nutrition for our family causes us to neglect the most basic (and often the most labor intensive) component of the process – dirt.

Some years ago, I was in wine country in Rutherford, California on a tour of an organic vineyard. As friends of the owner, our group was invited on a personal tour through the vegetable garden and then out into the vineyard. While at the edge of the property, the proud vintner grabbed a shovel that had been left resting on a fence line and handed it to a member of our party. He asked her to scoop a shovel-full of soil from between the rows of cabernet. She gently pushed the spade into the ground and came up with a rich, dark, loamy scoop of the subterranean ecosystem. We were each asked to grab a handful and run it through our fingers, to smell it and describe it. The soil was alive. It smelled earthy and moist, felt warm and sifted smoothly between our fingers.

The vintner then asked the woman from my tour group to walk ten steps over the property line into the neighboring, non-organic vineyard and take a scoop-full of their soil. The tip of the shovel bounced off the hard-packed dirt with a metallic clang. He explained to us how this was the direct result of using chemical fertilizers versus promoting a living, rich biosphere in the soil and surrounding environment. While the purpose that day was to promote the full flavor of their organic cabernet sauvignon (which I tested and retested to the greatest extent of my abilities), the same principals apply to all cultivation.

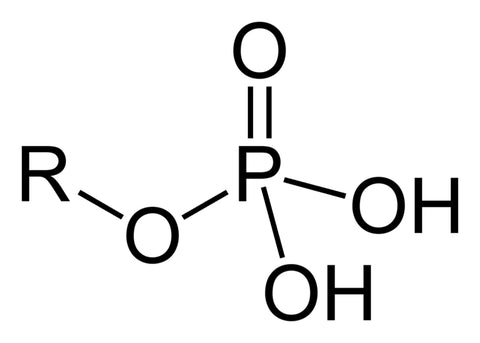

FERTILIZERS come in two basic flavors – chemical and organic. Fertilizers are used when the soil’s natural nutrient density is not enough to sustain the growth of the plants being cultivated. This is even more crucial in the case of vegetables and other food plants because of the rapid rate at which they grow.

Chemical fertilizers are made by isolating and concentrating the primary nutrients Nitrogen, Phosphate and Potash from natural ingredients through mechanical or chemical processes. Because you don’t need to wait for natural processes to break them down, they are immediately available for use by the plants. While this provides you with the ability to be extremely accurate in their application, it does nothing for the soil itself. In fact, the high concentrations and application methods often result in the complete destruction of the local soil ecology and can even leach into neighboring soil and ground water. This hard-packed, dense dirt prevents the plants from developing a healthy, deep root structure, making them reliant upon frequent reapplication of the chemical fertilizers, increasing water runoff and killing beneficial microbes which would otherwise create and store additional nutrients for the plants.

Organic fertilizers, by contrast, are derived from naturally occurring ingredients which have undergone little to no processing. They are sourced from mineral and biological materials such as salts (Epsom, saltpeter), fish emulsion, bone and blood meal, decomposed plant material and animal manure. Since the nutrients in organic materials are locked in the biological or chemical structures, they are typically slow-release fertilizers requiring natural processes (chemical and biological) to break them down. Some of these processes include exposure to sun, air and water, microbial fermentation, and invertebrate digestion (worms and insects).

Organic fertilizers can be further described in two flavors of their own: “hot” and “cold”. A “hot” fertilizer is one which has a high ratio of the three key nutrients (nitrogen “N”, phosphate “P” and potash “K”) to their carbon and moisture content. The high concentration of nitrogen can “burn” the plants, causing withering of leaves, stunted growth and death. Because of this, hot fertilizers need to first be composted with other carbon-rich materials such as straw, wood chips or other plant matter thereby allowing natural processes to break down and distribute the nutrients at lower concentrations throughout the whole of the material. Alternately, “cold” fertilizers have a much higher ratio of carbon and moisture to N, P and K, which allows them to be placed right onto or mixed into the planting area without first being composted.

As demonstrated by my alcohol fueled lesson in Northern California’s wine country, organic fertilizers are far superior to chemical fertilizers, primarily due to their additional benefit of providing composition – organic and inorganic – to the soil, which helps to hold in moisture, provide structure, and create a healthy ecological niche for microbes and other life. A chemical fertilizer, due to its caustic concentration, can kill any piece of the subterranean biosphere and collapse the entire local web of life in the single metallic clank of a shovel.

Which brings us to rabbit poop.

RABBIT POOP REALLY IS THE SHIT. As reflected in the table below, it’s saturated in nitrogen that promotes healthy leaf growth, high in phosphorous which is needed for flowering and setting fruit or vegetables, and contains many beneficial trace elements such as calcium, magnesium, boron, zinc, manganese, sulfur, copper, and cobalt. Because it is a cold fertilizer, its application directly to the soil provides excellent structure.

NUTRIENT BREAKDOWN OF SOME COMMON MANURES:

| MANURES | % NITROGEN | % PHOSPHATE | % POTASH |

| Rabbit (fresh) | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.6 |

| Bat | 6.0 | 9.0 | 3.0 |

| Cow (fresh) | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Cow (dry) | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| Chicken (fresh) | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Chicken (dry) | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Hog (fresh) | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Hog (dry) | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| Horse (fresh) | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Turkey (fresh) | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

© Erv Evans | Consumer Horticulturist | NC State University

For me, one of the key elements of sustainable permaculture on any scale is simplicity. I love rabbit poop because it is readily available (assuming one has rabbits (or access to them) – the benefits of which I will explore in a future post), requires no curing time before use, doesn’t smell and is packaged into little skittles of convenience. Worms love it too! I sprinkle mine directly around the base of the plant. As I water, the decomposing manure mulches into the soil in a perfect slow release throughout the growing season.

APPLICATION METHODS:

- Direct application of pellets

- Compost tea

- Compost pile

- Worm towers

RISKS:

- Minimal disease/parasite risk as with similar manures.

BENEFITS:

- Plant nutrition

- Waste disposal

- Rabbit meat

- Worm cultivation

References:

http://crossroadsrabbitry.com/rabbit-manure-info/

http://www.ces.ncsu.edu/depts/hort/consumer/quickref/fertilizer/nutrient_content.html

http://riseandshinerabbitry.com/2012/03/31/the-benefits-and-uses-of-rabbit-manure/